Blog

A selection of opinion pieces, short essays, and reviews originally written for The Philosophers' Magazine, The Conversation, Times Higher Education, Philosophy Now, Medium, etc.

English is the language of analytic philosophy. 97% of citations in prestigious analytic philosophy journals are of works written in English, and 96% of the journals’ board members reside in English-speaking countries. That might be simply because of English being the world’s common language, but it’s having a detrimental effect on analytic philosophy itself. Deprived of the perspectives of philosophical traditions written in other languages and excluding those philosophers whose English or type of prose doesn’t pass the test of the journals’ gatekeepers, analytic philosophy has found itself in a state of decadence. From Socrates and Plato to Hume and Kant, and from Arendt to Wittgenstein, none would fit the current stereotypes of analytic philosophy. Filippo Contesi, Louise Chapman and Constantine Sandis offer some solutions to this contemporary malaise. Read the essay on IAI TV

Bob Dylan did not die young. That still seems a surprise. Dylan himself has reflected a number of times about his cheating of death, toying with concepts of transfiguration and rebirth. From early on, biographers have recorded Dylan’s thoughts on his own death, speculating what it might mean for him to grow old. At the close of his landmark 1986 biography, No Direction Home – The Life and Music of Bob Dylan, Robert Shelton wondered what Dylan’s future career might be like. Would his creativity come to an abrupt end like that of Rimbaud, or would it flourish in late age, like that of Yeats? If once an open question, the answer has been clear since 1997’s Time Out of Mind. Dylan at 80, reflects on the evolving creativity across various stages of Dylan’s life and career, from a youthful Guthrie jukebox to elderly statesman with the blood of the land in his voice. On his latest album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, the Blakean song ‘I Contain Multitudes’ serves as a piece of retrospective self-reflection upon Dylan’s own many-sidedness, in turn refracted into the many songs on the album. Heartfelt love songs, rowdy blues, mournful reflections on the political past and present, and ruminations on the end of things represent and deepen Dylan’s repertoire ever since Another Side of Bob Dylan. 2021 marks Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday and his 60th year in the music world. It invites us to look back on his career and the multitudes that it contains. Is he a song and dance man? A political hero? A protest singer? A self-portrait artist who has yet to paint his masterpiece? Is he Shakespeare in the alley? The greatest living exponent of American music? An ironsmith? Internet radio DJ? Poet (who knows it)? Is he a spiritual and religious parking meter? Judas? The voice of a generation or a false prophet, jokerman, and thief? Dylan is all these and none. We can now consider what it means for Dylan to be entering his seventh decade as a recording artist. If this book is about anything, it is about reflecting on Dylan at 80. How is he? How is his art? Does he still embody the themes and styles of his younger self, or has he developed a late style that won’t look back? The essays in this book explore the Nobel laureate’s masks, collectively reflecting upon their meaning through time, change, movement, and age. Read more on Medium

Philosophy has a language problem. A recent study by Schwitzgebel, Huang, Higgins and Gonzalez-Cabrera(2018) found that, in a sample of papers published in elite journals, 97% of citations were to work originally written in English. 73% of this same sample didn’t cite any paper that had been originally written in a language other than English. Finally, a staggering 96% of elite journal editorial boards are primarily affiliated with an Anglophone university. This is consistent with earlier data suggesting that journal submissions from countries that are outside the Anglophone world and Europe have disturbingly low chances of being accepted. Unless one takes the absurd view that the data reflects who does the best philosophy and where they do it, this is prima facie cause for concern. The recently published “Barcelona Principles for a Globally Inclusive Philosophy” aim at addressing a “structural inequality between native and non-native speakers”, and call on philosophers to take steps like including non-native speakers on editorial boards and not giving “undue weight to their authors’ linguistic style, fluency or accent”. Schwitzgebel et al.’s study doesn’t tell us what percentage of papers originally written in English were by non-native speakers. However, as Schwitzgebel’s and others’ data suggest, the academic pipeline of Anglophone philosophy is overwhelmingly self-confined within elite Anglophone institutions. Indeed, additional data point to a structural inequality between native and non-native speakers. For instance, preliminary data suggest that journal academic reviewing is in general biased against “non-native-like English” prose and in fact non-native speakers of English appear to be much more poorly represented in prestigious philosophy departments than in equally prestigious scientific departments. Read more on Medium

Moral particularism is often defined as the view that there are no universal moral principles. This is sometimes defended by appeal to examples, such as that of lying to a Nazi officer. Defenders of moral principles either bite the bullet and insist that lying is always wrong, or revise the principle in question to include clauses such as ‘unless a murderous Nazi is asking questions’. Nobody knows how many clauses a principle can withstand before it becomes meaningless. Luckily, it doesn’t matter. The real issue doesn’t concern the possibility of true moral generalisations, but whether such principles can themselves provide us with reasons for action. Particularists answer this question negatively, holding further that moral reasoning is hindered by strict adherence to even the best of moral codes. Moral particularism is often defined as the view that there are no universal moral principles. This is sometimes defended by appeal to examples, such as that of lying to a Nazi officer. Defenders of moral principles either bite the bullet and insist that lying is always wrong, or revise the principle in question to include clauses such as ‘unless a murderous Nazi is asking questions’. Nobody knows how many clauses a principle can withstand before it becomes meaningless. Luckily, it doesn’t matter. The real issue doesn’t concern the possibility of true moral generalisations, but whether such principles can themselves provide us with reasons for action. Particularists answer this question negatively, holding further that moral reasoning is hindered by strict adherence to even the best of moral codes. Read more on Medium

There is a famous thesis in moral philosophy that has come to be known as the ‘guise of the good’. According to this ancient doctrine — which remains popular to this day — we only ever desire things that we perceive as being good, in at least some respect. As Socrates puts it in Plato’s Meno: “nobody wants to be wretched”. The problem is that what we take to be good may only be so apparently. We accordingly often pursue terrible things, mistaking them for good. On a stronger version of the doctrine, we not only desire the apparent good but always act on such desires. Taken to the extreme, it states that all wrongdoing is but a form of ignorance. In a virtually-unnoticed, fascinating twist, Friedrich Nietzsche turns the guise of the good thesis on its head. Indeed, on his account, it would be more appropriate to talk of the good of the guise: we do not desire things because we think of them as good, but, on the contrary, perceive things to be good precisely because we desire them. To think otherwise is to fall prey to the more general ‘great error’ of confusing cause and effect (Twilight of the Idols, V). Nietzsche’s insight into human nature is that things acquire their perceived worth in proportion to how much we covet and strive after them; the tougher the achievement, the more we value the thing achieved... Read more on Medium

In the wake of COVID-19, memes asserting that, for the first time in history, we could save the world by doing absolutely nothing went (ahem) viral. The notion that one can achieve a great good by doing bugger all is blindingly attractive. How cool would it be if heroism not only begins at home, but gets to stay there, putting its feet up, watching Netflix, and occasionally donning a mask to pop out for emergency pizza? Not all heroes get to wear masks or stay at home though, because not all heroes can afford masks, let alone the privilege of social-distancing or a home in which to lockdown. Many live in small cramped spaces and/or desperately relying on low incomes from manual labour, such as driving a bus, stacking shelves, or delivering food parcels to those of us staying at home doing nothing ...read more in The Philosophers' Magazine

In Gail Carson Levine’s fairy tale Ella Enchanted , the imprudent fairy Lucinda casts a spell on Ella which causes her to ‘always be obedient’, her behaviour triggered by commands which she literally cannot resist ‘obeying’. Her orders are for reasonably discrete actions such as fetching people items of food but are clearly extendable to complex activities like going on a three-weak horseback trip across the country side. Commands to the do the latter sort of thing leave Ella sufficient space to choose to perform any small acts which aren’t in conflict with her wider instructions, until she’s further commanded otherwise (priority is always given to the earliest command that’s yet to be fulfilled). Here’s how the protagonist describes her own terrible predicament: Anyone could control me with an order. It had to be a direct command, such as “Put on a shawl,” or “You must go to bed now” […] against an order I was powerless […] I could never hold out for long (9). The curse envisioned by Levine (who majored in philosophy) transforms a human being into a semi-automaton whose behaviour is easily manipulated through voice-activation. While ultimately powerless, she is nonetheless able to briefly resist any command that doesn’t explicitly request for immediate action. Ella lacks the freedom to do as she wills, insofar as her will is paralysed each time she is ordered to do something... Continue reading on Medium

The final story in Angela Carter’s 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber begins with a sentence replete with provisos: Could this ragged girl with brindled lugs have spoken like we do she would have called herself a wolf, but she cannot speak, although she howls because she is lonely — yet ‘howl’ is not the right word for it, since she is young enough to make the noise that pups do, bubbling, delicious, like that of a panful of fat on the fire (1979:140). In her introduction to the the 2006 Vintage reprint , Helen Simpson writes that Carter once joked that ‘the advantage of including animal protagonists in her work was that she did not have to make them talk’. But speak some of them do — and in this case it is a human who cannot speak, or indeed barely even howl Had she been able to speak (or otherwise communicate) as ‘we’ do, the reader is told, she would not have identified herself as human but as a wolf. What a deceptively simple thought this is. The we in question might at first appear to refer to ‘us’ humans , a set to which the reader presumably belongs — bar Carter’s writings being enjoyed by alien species. But even then, it presumably doesn’t include toddlers and other human beings who lack the required communicative skills... Continue reading on Medium

F orget the Turing test. Alan said it best in a neglected paragraph of the original paper in which he first proposed his test: The original question, “Can machines think?” I believe to be too meaningless to deserve discussion. Nevertheless I believe that at the end of the century the use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted (442). Turing’s 1950 prediction was not that computers would be able to think in the future but that we would talk of computers thinking and that, once this happened, what we meant by the term would have morphed in such a way that it would be pretty uncontroversial to say that machines think. Our use of the term has indeed loosened to the point that attribution of thought to even the most basic of machines has become common parlance, at least outside the wretched confines of the philosophy classroom, in which no claim is too obvious... Continue Reading on Medium

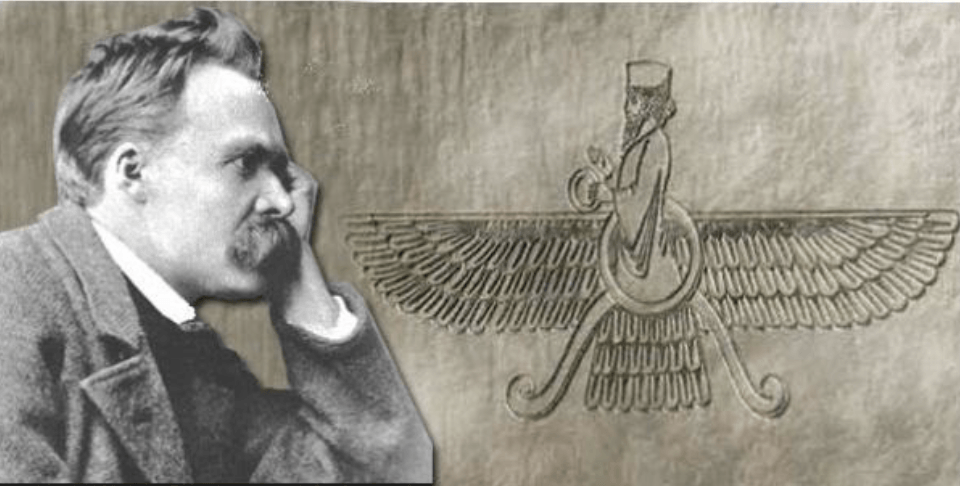

In 1885 Nietzsche finished writing Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in which he has the prophet proclaim many Nietzschean ideas in parables and epiphets. Constantine Sandis asks why Nietzsche particularly chose Zarathustra. In M. Night Shyamalan’s superhero film Unbreakable , the fragile-boned Elijah believes that somewhere out there he has an enemy with the exact opposite property, whom he eventually identifies as the ‘unbreakable’ security guard David Dunn. A similar kind of reasoning led Nietzsche to name the protagonist of his religious parody Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-5) after Zoroaster (‘Zarathustra’ is a Westernised version of the name). Nietzsche viewed the Persian prophet as his arch rival: an opponent of similar power and stature, whom he admired but could never fully overcome. In the character of ‘Zarathustra’, Nietzsche attempts to create his own spokesman worthy of Zoroaster’s greatness. As the psychologist Carl Jung put it in his lectures on Nietzsche’s Zarathustra (1934-9), while it is true that “Nietzsche chose a most dignified and worthy model for his wise old man,” he also took him to be “the founder of the Christian dogma” [of moral objectivity] that Nietzsche so vehemently opposed. He also notes that Zarathustra’s recorded age in Thus Spoke Zarathustra is the same as “the legendary age of Christ when he began his teaching career.” The Mask of Zoroaster Jung also suggested that Zarathustra manifests a second personality for Nietzsche, which was perhaps awaiting an opportunity to be expressed. This reading is supported by Nietzsche’s claim that during one of his lakeside walks in Sils-Maria in Switzerland, in July 1881, he experienced a vision concerning Zarathustra and the nature of inspiration. He describes the experience as follows in his posthumously-published autobiographical Ecce Homo (which, among other things, is a parody of Wagner’s self-indulgent My Life , which Nietzsche described as ‘an agreed-upon fable’... Read more in Philosophy Now An longer version was published in Hamazor 2013 Issue 1 as 'Why Did Nietzsche Choose Zarathustra As a Mask?'