In Conversation with Nassim Taleb

Knowledge and Scepticism

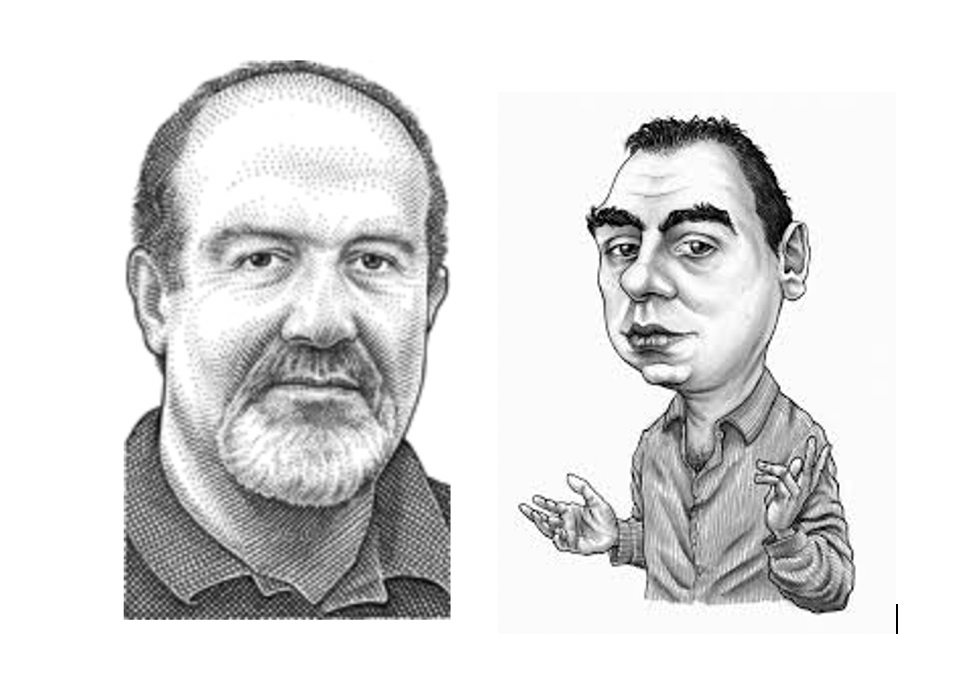

Nassim Nicholas Taleb has had a run-away success with The Black Swan , a book about surprise run-away successes. Constantine Sandis talks with him about knowledge and scepticism.

CS: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing,” the Greek poet Archilochus once wrote. Isaiah Berlin famously used this saying to introduce a distinction between two different kinds of thinkers: those who “pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory,” and those who relate everything to a “single central vision… a single, universal, organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance.” Nassim, I think you would see yourself as an intellectual hedgehog. I have heard you describe your big idea, which you have had from childhood, as the view that the more improbable an outcome is, the higher its impact (and vice versa ). Many controversial corollaries follow from this one claim, and you have recorded some of the most important in numerous essays, as well as in your books Fooled by Randomness and The Black Swan . These thoughts range from remarks on the perils of socioeconomic forecasting, to views on epistemology, agnosticism, explanation and understanding, the dynamics of historical events, and perhaps most importantly, advice on where to live and which parties to attend.

As I find myself in the awkward position of wishing to endorse almost all of the corollaries while fiercely disagreeing with the large idea from which they stem, I would like to ask you whether you really think that all improbable events have a high impact, and that all high impact events are improbable, or whether this is simply a misleading way of describing your insight? Are you happy to allow for counterexamples?

NNT: My core idea is about the effect of non-observables in real life. My focus is on the errors which result: how the way we should act is affected by things we can’t observe, and how we can make decisions when we don’t have all the relevant information.

My idea concerns decision-making under conditions of uncertainty, dealing with incomplete information, and living in a world that has a more complicated ecology than we tend to think. This question about justifiable responses to the unknown goes way beyond the conventionally-phrased ‘problem of induction’ and what people call ‘scepticism’. These classifications are a little too tidy for real life. Alas, the texture of real life is more sophisticated and more demanding than analytical philosophy can apparently handle. The point is to avoid ‘being the turkey’. [ There is a philosophical parable about a turkey who on the basis of daily observations concludes that he’s always fed at 9am. On Christmas Eve he discovers this was an overhasty generalisation – Ed. ] To do so you have to stand some concepts on their head – like your concept of the use of beliefs in decision making...

Read more in Philosophy Now